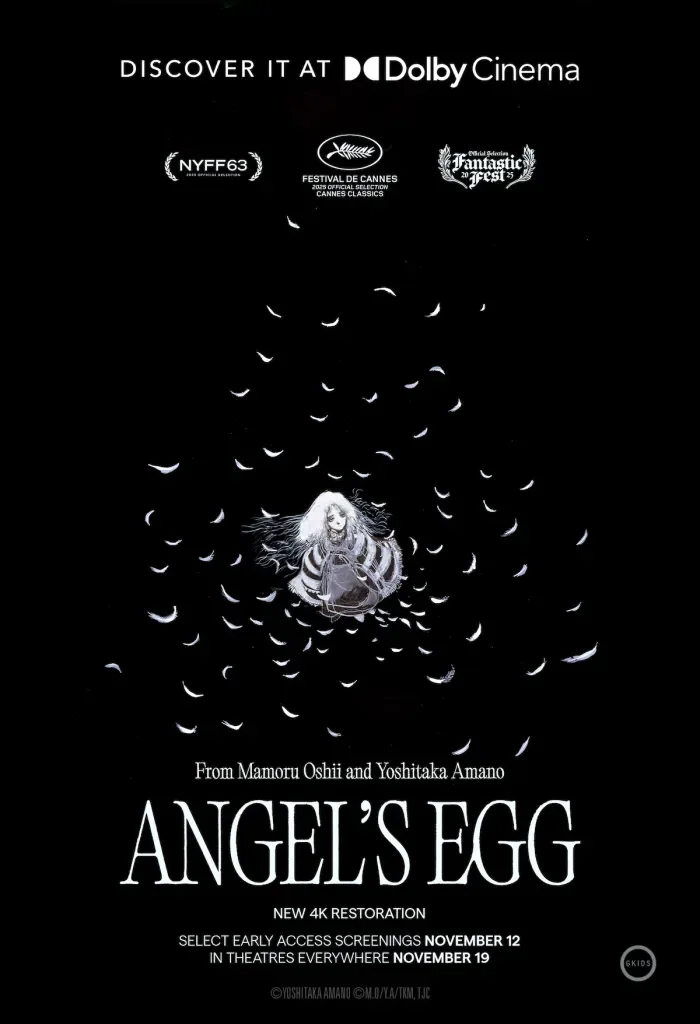

JQ Magazine: ‘Angel’s Egg’ 4K Restoration: A Reverie Reborn in Dolby Cinema

By JQ magazine editor Justin Tedaldi (CIR Kobe-shi, 2001-02) with Vlad Baranenko (Saitama-ken, 2000-02) for JQ magazine. Justin has written about Japanese arts and entertainment for JETAA since 2005. For more of his articles, click here.

“You walk into a dark auditorium, sit among strangers, and listen to a city where even shadows seem to pray. You wait for a girl to decide whether to keep her egg whole. The credits roll. In the quiet afterward, you realize the restoration hasn’t ‘solved’ the movie; it has preserved its questions.” (GKIDS)

Mamoru Oshii’s Angel’s Egg is one of those films that people talk about in a lowered voice, as if it were a mystery that might vanish if confronted too directly. It is a film of austere beauty and radical quiet—70-odd minutes of shadowed corridors, abandoned cathedrals, fossilized leviathans, and two nameless travelers: a girl who cradles a giant egg as if it were her entire future, and a boy who cannot stop asking what’s inside.

Released in 1985 and long unavailable through official channels in North America, Angel’s Egg has gathered its legend through bootleg tapes, festival whispers, and the occasional late-night screening. Now, four decades on, it returns today (Nov. 19) in theaters nationwide in a new 4K restoration supervised by Oshii and presented nationwide by GKIDS, which included Dolby Cinema early access engagements before the general theatrical rollout. For a film that has lived so much of its life in the margins, the chance to experience it in a calibrated premium room with Dolby Vision and Atmos support feels almost paradoxical—and absolutely right.

This anniversary run isn’t just a new coat of paint. The restoration—which debuted on the 2025 festival circuit and now arrives coast to coast—was reconstructed from the original 35mm materials, with a Dolby Cinema version created alongside a rebuilt soundtrack that expands the original mono presentation into 5.1 and Dolby Atmos options. That last detail may raise eyebrows for purists, but in practice the approach respects the film’s fundamental quietude; it simply gives the silence more dimensions.

To remember Angel’s Egg in the context of anime history is to remember how unstandardized the medium felt in the mid-1980s. It premiered in a decade when the OVA market was exploding and when directors like Oshii and artists like Yoshitaka Amano (Final Fantasy, Vampire Hunter D) were testing the boundaries of animation’s visual grammar. The film’s surface—textured stone, dripping water, the faint pulse of bio-mechanical curiosities—speaks in symbols rather than exposition. There is barely any dialogue. The camera (or rather, Oshii’s implied lens) prefers long lateral moves, as if pacing the nave of an endless church, and the compositions are arranged like prints: light carved out of darkness, characters dwarfed by architecture, the egg always nestled in white cloth at the frame’s center.

©YOSHITAKA AMANO © Mamoru Oshii/Yoshitaka Amano/Tokuma Shoten, Tokuma Japan Communications. All Rights Reserved.

When viewers call the film “obscure,” they don’t just mean it’s hard to find; they mean it resists the usual ways we talk about plots. If Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell (1995) became the textbook for cyber-philosophy in animation, Angel’s Egg is the poem scrawled in the margins. The imagery anticipates later techno-gothic strains of anime, but without the anchor of a conventional narrative. In this sense, its return to theaters matters historically: one rarely sees repertory engagements for 1980s anime outside of a handful of well-known titles, and the film’s own distributors underscore how rarely screened it’s been in any official capacity. Seeing it at scale isn’t a curiosity; it’s an act of historical restoration.

Oshii’s collaboration with Amano yields a film that looks simultaneously medieval and futuristic. Statues of saints are strapped to rolling platforms and carted through fog-wet streets; hunters hurl harpoons at shadow-fish that pass across stone facades like projected ghosts; the girl and the boy ride a gargantuan, half-submerged machine that could be a cathedral or a vessel or a fossilized beast. The film’s religious aura—crosses, chalices, a literal ark—threads through its central question: does faith require the egg to remain closed, or the courage to break it? The boy, carrying a rifle and speaking in riddles, keeps needling: “What’s inside?” The girl maintains her vigil.

What’s remarkable, especially on a big screen, is how the movie makes time feel tactile. Shots hold until your breathing matches the drip of water; the rhythm of footsteps through an empty hall becomes as musical as Kenji Kawai’s glassy, ascetic score. And then, at intervals, Oshii punctures the stillness with kinetic episodes: a barrage of thrown spears; a dissolve-drunk montage of monuments and bones; an unforgettable nocturne of the boy swinging the egg like a hammer. These moments carry a kind of moral vertigo that’s hard to feel at home; they need the dark, the scale, the sense that the film surrounds you.

©YOSHITAKA AMANO © Mamoru Oshii/Yoshitaka Amano/Tokuma Shoten, Tokuma Japan Communications. All Rights Reserved.

Because Angel’s Egg is all about contrast—light etched into shadow; tiny human voices against cavernous space—the Dolby Cinema presentation becomes more than a novelty banner. In Dolby Cinema auditoriums, Dolby Vision dual-laser projection delivers much higher dynamic range and color volume than standard digital cinema packages, targeting contrast ratios orders of magnitude greater than conventional systems, In practical terms, that means that black can look like true black, not a charcoal wash, while while highlights—lamplight on water, a halo edging the egg—retain texture without blooming. Angel’s Egg lives in those thresholds. The restored 4K scan accentuates the grain and ink lines, but Dolby Vision’s tone-mapping splendidly preserves Oshii’s original vision: The palette still favors bruised blues, desaturated violets, and candlelit ambers rather than modern neon pop.

The audio side benefits from the Atmos-enhanced rebuild: Dolby Atmos allows sound-objects to be placed discretely around the auditorium (including overhead), rather than merely mixed into traditional 5.1 or 7.1 channels. Festival notes and coverage credit IMAGICA and Sony among the aural collaborators, and even a film as quiet as Angel’s Egg leverages this. Water doesn’t just “fill” the room; it slips from a particular corner to a drain behind you. When the hunters fling their harpoons at phantom fish, the streaks of metal cross the auditorium in a slow, almost ceremonial arc; the object-based Atmos placement maps that movement rather than merely swelling in volume. The net effect harmonizes with Oshii’s austerity rather than overpowering it.

Context matters for a release like this. After Angel’s Egg, Oshii would pursue more explicitly political and philosophical concerns in Patlabor 2 and Ghost in the Shell, building an international reputation as one of animation’s foremost, if not inscrutable, futurists. Yet Angel’s Egg remains his most cryptic confession: a film often read through the lens of a crisis of faith and the director’s personal history. You don’t need biographical knowledge to feel its ache. The film’s childlike simplicity—girl, egg, boy—wraps around dense, arguably theological questions: Is belief a shelter or a prison? Is knowledge an act of preservation or violence? By refusing to annotate itself, the movie preserves a sacred ambiguity, a quality that can be smothered by poor transfers or casual viewings, but thrives in the communal experience of the theatrical space.

©YOSHITAKA AMANO © Mamoru Oshii/Yoshitaka Amano/Tokuma Shoten, Tokuma Japan Communications. All Rights Reserved.

It’s hard to overstate how unusual this is for 1980s anime. Aside from canonized features by Hayao Miyazaki and a few cult juggernauts, American cinemas seldom mount national engagements of catalog anime from the era. Trade coverage announcing this restoration uniformly stresses just how rarely screened Oshii’s film has been, and that framing isn’t just hype: it reflects a real gap in repertory programming that favors later digital titles or a narrow slice of “safe” classics. This nationwide rollout of Angel’s Egg therefore functions as both a celebration and a test case—proof that there’s an audience for the more esoteric corners of anime history when the presentation honors the material. Accordingly, this release is being treated as a major theatrical event, not a curiosity in a single-screen niche.

Animation history, of course, doesn’t change because a movie gets spruced up picture and sound. But histories are built out of viewings, and viewings require access. Oshii’s film has lived too long as a suggestion; now it can be an encounter. You walk into a dark auditorium, sit among strangers, and listen to a city where even shadows seem to pray. You wait for a girl to decide whether to keep her egg whole. The credits roll. In the quiet afterward, you realize the restoration hasn’t “solved” the movie; it has preserved its questions.

Even if you know Angel’s Egg by heart, this anniversary presentation will show you textures you’ve never seen and give you space to feel the film’s peculiar gravity. More than a prestige polish, the release is a statement that the canon of 1980s anime reaches far beyond the usual suspects—and that audiences will turn out to greet it when exhibitors meet the work halfway. For those of us who have kept the movie alive through anecdote and artifact, there is an ebullient joy in finally watching it step into bright, respectful light. If the question the film poses is whether we can hold onto mystery without breaking it, this release answers by example. The egg remains the egg. We simply see it more clearly now—cupped in careful hands, glowing softly against the dark. And in Dolby Cinema, that glow feels like a benediction.

©YOSHITAKA AMANO © Mamoru Oshii/Yoshitaka Amano/Tokuma Shoten, Tokuma Japan Communications. All Rights Reserved.

Angel’s Egg is in theaters everywhere. For tickets and showtimes, click here.

For more JQ articles, click here.